Effect of 12-Week Aerobic Exercise Training on Chemokine Ligands and Their Relative Receptors in Balb/C Mice with Breast Cancer

Keywords:

Cancer, Physical Activity, Chronic Inflammation, Chemokines, Oxidative Stress, EnzymesAbstract

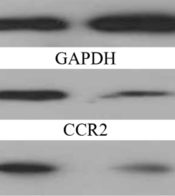

Background: Some chemokines like C C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 2 and 5 and their receptors (CCR) 2 and 5 are mediators of chronic inflammation and cancer development. Moreover, physical exercise can increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes. However, its effect on cancer cells has not been reported at present. Objectives: Therefore, the present study aimed to ascertain the effect of 12-week aerobic exercise training (AET) on CCL2, CCR2, CCL5, and CCR5 in mice with breast cancer. Methods: Sixteen Balb/c mice aged 4 - 5 weeks (n = 16; approximate weight: 18 ± 2 g) were divided into two groups: AET group (AETG) and control group (CG) (n = 8 per group). The AETG performed 12-week treadmill running at 18 m/min for 40 min and five times a week. Plasma levels of CCL2 and CCL5 were measured by ELISA, and the CCR2 and CCR5 were evaluated by Western blotting. Two independent sample t-test was applied to compare the differences between AETG and CG. Results: The analysis displayed after 12 weeks showed a significant reduction in AETG compared to CG in CCL2 (3.94 ± 1.12 vs. 15.40 ± 3.29 pg/mL; P = 0.001), CCR2 (0.56 ± 0.19 vs. 1.00 ± 0.001; P = 0.002), CCL5 (138.59 ± 15.72 vs. 267.57 ± 49.06 ng/mL; P = 0.001) and CCR5 (0.36 ± 0.12 vs. 1.00 ± 0.001; P = 0.001), respectively. Conclusions: We concluded that one of the main mechanisms of a positive effect of exercise on breast cancer is reducing the inflammation via CCL2 and CCL5 and their related receptors CCR2 and CCR5, respectively. Since these molecules can be triggered off oxidative stress and tumorigenesis, these results can pave the way for further studies in this field.

Downloads

References

1. Akbari A, Razzaghi Z, Homaee F, Khayamzadeh M, Movahedi M, Akbari

ME. Parity and breastfeeding are preventive measures against breast

cancer in Iranian women. Breast Cancer. 2011;18(1):51–5. [PubMed ID:

20217489]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-010-0203-z.

2. Burkman RT. Berek & Novak’s Gynecology. Jama. 2012;308(5):516.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.308.5.516.

3. Allavena P, Sica A, Solinas G, Porta C, Mantovani A. The

inflammatory micro-environment in tumor progression: the role of tumor-associated macrophages. Crit

Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66(1):1–9. [PubMed ID: 17913510].

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.07.004.

4. Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357(9255):539–45. [PubMed ID: 11229684].

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04046-0.

5. Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature.

2002;420(6917):860–7. [PubMed ID: 12490959]. [PubMed Central

ID: PMCPmc2803035]. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01322.

6. Suzuki K. Cytokine Response to Exercise and Its Modulation. Antioxidants. 2018;7(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7010017.

7. Ruhee RT, Suzuki K. The Integrative Role of Sulforaphane in Preventing Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Fatigue: A Review

of a Potential Protective Phytochemical. Antioxidants (Basel).

2020;9(6). [PubMed ID: 32545803]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC7346151].

https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9060521.

8. Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med.

2010;49(11):1603–16. [PubMed ID: 20840865]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc2990475]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006.

9. Crujeiras AB, Díaz-Lagares A, Carreira MC, Amil M, Casanueva FF.

Oxidative stress associated to dysfunctional adipose tissue: a potential link between obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and breast

cancer. Free Radic Res. 2013;47(4):243–56. [PubMed ID: 23409968].

https://doi.org/10.3109/10715762.2013.772604.

10. Ben-Baruch A. The multifaceted roles of chemokines in malignancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(3):357–71. [PubMed ID:17016763].

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-006-9003-5.

11. Conti I, Rollins BJ. CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1) and

cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14(3):149–54. [PubMed ID: 15246049].

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.009.

12. Zlotnik A. Involvement of chemokine receptors in organ-specific

metastasis. Contrib Microbiol. 2006;13:191–9. [PubMed ID: 16627966].

https://doi.org/10.1159/000092973.

13. Palomino DC, Marti LC. Chemokines and immunity. Einstein (Sao

Paulo). 2015;13(3):469–73. [PubMed ID: 26466066]. [PubMed Central

ID: PMCPmc4943798]. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082015rb3438.

14. Ben-Baruch A. The Tumor-Promoting Flow of Cells Into, Within

and Out of the Tumor Site: Regulation by the Inflammatory

Axis of TNFα and Chemokines. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5(2):151–

64. [PubMed ID: 22190050]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc3399063].

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12307-011-0094-3.

15. Ernst CA, Zhang YJ, Hancock PR, Rutledge BJ, Corless CL, Rollins

BJ. Biochemical and biologic characterization of murine monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1. Identification of two functional domains.

J Immunol. 1994;152(7):3541–9. [PubMed ID: 8144933].

16. Fife BT, Huffnagle GB, Kuziel WA, Karpus WJ. CC chemokine

receptor 2 is critical for induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2000;192(6):899–905.

[PubMed ID: 10993920]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc2193286].

https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.192.6.899.

17. Huang DR, Wang J, Kivisakk P, Rollins BJ, Ransohoff RM. Absence of

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in mice leads to decreased local macrophage recruitment and antigen-specific T helper cell type 1

immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.

J Exp Med. 2001;193(6):713–26. [PubMed ID: 11257138]. [PubMed Central

ID: PMCPmc2193420]. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.193.6.713.

18. Svensson S, Abrahamsson A, Rodriguez GV, Olsson AK, Jensen L,

Cao Y, et al. CCL2 and CCL5 Are Novel Therapeutic Targets for

Estrogen-Dependent Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(16):3794–

805. [PubMed ID: 25901081]. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-

0204.

19. Jiménez-Sainz MC, Fast B, Mayor FJ, Aragay AM. Signaling pathways for monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-mediated extracellular

signal-regulated kinase activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64(3):773–82.

[PubMed ID: 12920215]. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.64.3.773.

20. Johnson Z, Power CA, Weiss C, Rintelen F, Ji H, Ruckle T, et

al. Chemokine inhibition–why, when, where, which and how?

Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32(Pt 2):366–77. [PubMed ID: 15046611].

https://doi.org/10.1042/bst0320366.

21. Mellado M, Rodríguez-Frade JM, Aragay A, del Real G, Martín AM, VilaCoro AJ, et al. The chemokine monocyte chemotactic protein 1 triggers Janus kinase 2 activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of the

CCR2B receptor. J Immunol. 1998;161(2):805–13. [PubMed ID: 9670957].

22. Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment.

Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):309–22. [PubMed ID: 22439926].

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022.

23. Soria G, Ben-Baruch A. The inflammatory chemokines CCL2 and

CCL5 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(2):271–85. [PubMed ID:

18439751]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.018.

24. Kershaw MH, Westwood JA, Darcy PK. Gene-engineered T cells for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(8):525–41. [PubMed ID: 23880905].

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3565.

25. Nobari H, Nejad HA, Kargarfard M, Mohseni S, Suzuki K,

Carmelo Adsuar J, et al. The Effect of Acute Intense Exercise on Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Smokers and

Non-Smokers. Biomolecules. 2021;11(2). [PubMed ID: 33513978].

https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11020171.

26. Roque AT, Gambeloni RZ, Felitti S, Ribeiro ML, Santos JC.

Inflammation-induced oxidative stress in breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2015;32(12):263. [PubMed ID: 26541769].

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-015-0709-5.

27. Parise G, Phillips SM, Kaczor JJ, Tarnopolsky MA. Antioxidant enzyme

activity is up-regulated after unilateral resistance exercise training

in older adults. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39(2):289–95. [PubMed ID:

15964520]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.024.

28. Repka CP, Hayward R. Oxidative Stress and Fitness Changes in Cancer

Patients after Exercise Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(4):607–

14. [PubMed ID: 26587845]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc4979000].

https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000821.

29. Trøseid M, Lappegård KT, Claudi T, Damås JK, Mørkrid L, Brendberg R,

et al. Exercise reduces plasma levels of the chemokines MCP-1 and IL-8

in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(4):349–

55. [PubMed ID: 14984925]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.006.

30. Shalamzari SA, Agha-Alinejad H, Alizadeh S, Shahbazi S, Khatib ZK,

Kazemi A, et al. The effect of exercise training on the level of tissue IL-6

and vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer bearing mice.

Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17(4):231–58. [PubMed ID: 24904714]. [PubMed

Central ID: PMCPmc4046231].

31. Al-Jarrah M, Pothakos K, Novikova L, Smirnova IV, Kurz MJ, StehnoBittel L, et al. Endurance exercise promotes cardiorespiratory rehabilitation without neurorestoration in the chronic mouse model

of parkinsonism with severe neurodegeneration. Neuroscience.

2007;149(1):28–37. [PubMed ID: 17869432]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc2099399]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.038.

32. Hou N, Ndom P, Jombwe J, Ogundiran T, Ademola A, MorhasonBello I, et al. An epidemiologic investigation of physical

activity and breast cancer risk in Africa. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(12):2748–56. [PubMed ID: 25242052].

https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-14-0675.

33. Soria G, Ofri-Shahak M, Haas I, Yaal-Hahoshen N, Leider-Trejo L,

Leibovich-Rivkin T, et al. Inflammatory mediators in breast cancer:

coordinated expression of TNFα & IL-1β with CCL2 & CCL5 and effects

on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:130.

[PubMed ID: 21486440]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc3095565].

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-130.

34. Mandal PK, Biswas S, Mandal G, Purohit S, Gupta A, Majumdar

Giri A, et al. CCL2 conditionally determines CCL22-dependent

Th2-accumulation during TGF-β-induced breast cancer progression. Immunobiology. 2018;223(2):151–61. [PubMed ID: 29107385].

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2017.10.031.

35. Carlin JL, Grissom N, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F, Reyes TM. Voluntary exercise blocks Western diet-induced gene expression of the

chemokines CXCL10 and CCL2 in the prefrontal cortex. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;58:82–90. [PubMed ID: 27492632]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc5352157]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2016.07.161.

36. Chiu HY, Sun KH, Chen SY, Wang HH, Lee MY, Tsou YC, et al.

Autocrine CCL2 promotes cell migration and invasion via PKC

activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin in bladder

cancer cells. Cytokine. 2012;59(2):423–32. [PubMed ID: 22617682].

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2012.04.017.

37. Saji H, Koike M, Yamori T, Saji S, Seiki M, Matsushima K, et al.

Significant correlation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

expression with neovascularization and progression of breast

carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92(5):1085–91. [PubMed ID: 11571719].

https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1085::aidcncr1424>3.0.co;2-k.

38. Goh J, Endicott E, Ladiges WC. Pre-tumor exercise decreases breast

cancer in old mice in a distance-dependent manner. Am J Cancer Res.

2014;4(4):378–84. [PubMed ID: 25057440]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc4106655].

39. Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst.

2012;104(11):815–40. [PubMed ID: 22570317]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc3465697]. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djs207.

40. Löf M, Bergström K, Weiderpass E. Physical activity and

biomarkers in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2012;73(2):134–42. [PubMed ID: 22840658].

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.07.002.

41. Suzuki K. Chronic Inflammation as an Immunological Abnormality and Effectiveness of Exercise. Biomolecules. 2019;9(6).

[PubMed ID: 31181700]. [PubMed Central ID: PMCPmc6628010].

https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9060223.

42. Na HK, Oliynyk S. Effects of physical activity on cancer prevention. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1229:176–83. [PubMed ID: 21793853].

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06105.x.

43. Amani-Shalamzari S, Aghaalinejad H, Alizadeh SH, Kazmi AR, Saei MA,

Minayi N, et al. [The effect of endurance training on the level of tissue

IL-6 and VEGF in mice with breast cancer]. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci.

2014;16(2):10–21. Persian.

44. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et

al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and

major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–86.

[PubMed ID: 25220842]. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29210.

45. Fong DY, Ho JW, Hui BP, Lee AM, Macfarlane DJ, Leung SS, et al. Physical

activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled

trials. Bmj. 2012;344. e70. [PubMed ID: 22294757]. [PubMed Central ID:

PMC3269661]. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e70.

46. Fernández Ortega JA, de Paz Fernández JA. Cáncer de mama y ejercicio

físico: Revisión. Hacia la Promoción de la Salud. 2012;17(1):135–53. Spanish.

47. Fairey AS, Courneya KS, Field CJ, Bell GJ, Jones LW, Mackey JR. Effects

of exercise training on fasting insulin, insulin resistance, insulin-like

growth factors, and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in

postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled

trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(8):721–7. [PubMed ID:

12917202].

48. Buss LA, Dachs GU. The Role of Exercise and Hyperlipidaemia in Breast

Cancer Progression. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2018;24:10–25. [PubMed ID:

29461968].

Downloads

Additional Files

Published

Submitted

Revised

Accepted

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.